Are We in a Bubble? - 25 Magazine: Issue 5

Crowded coffee spaces and firework acquisitions are making the specialty coffee industry nervous enough to start using the word “bubble.”

At the April 2017 Re:co Symposium, an annual event hosted by the Specialty Coffee Association, a panel debated the question: are we in a coffee bubble? Panelists DAN MCCLOSKEY and JANICE ANDERSON, using their extensive experience mapping the growth of specialty coffee across the US, offer their perspective on the state of the market in Issue 05 of 25.

As we move into the second quarter of 2018, the specialty coffee industry seems nervous. The third wave, once a coffee form that was new and cool, seems to be showing up to large, second wave brands like a chain competitor. It’s been decades since the days when specialty coffee was a revolution against the tyranny of blends, mechanization, and sugar drinks. In even more recent history, worries about the initial morals of profit taking has given way to the wholesale trading of brands between large consumer goods companies.

Acquisitions and investments evoke the feeling that the “special” is becoming corporate. Some specialty coffee companies now share family trees with mainstream consumer products like yogurt, lotion, and laundry detergent. The year 2017 delivered the largest specialty coffee company acquisition on record with the re-trading of Blue Bottle to Nestlé for a staggering $425 million.

Meanwhile, there seems to be a “third wave playbook” that has been passed around to any entrepreneur with a few extra hundred grand and a sweet location. Certain places, once the source of unique coffee experiences (Melbourne, London, Dublin, LA, Chicago – just to name a few), are super saturated with coffee companies. Everyone is talking about their coffees’ provenance. Everyone has an $18k espresso machine. Everyone can do latte art. Everyone has a passionate mission, a direct relationship with the grower, and a commitment to deliver the highest quality.

Should specialty be worried? Is the bubble going to pop? The quick answer, from our perspective, is no, we are not in a coffee bubble. But, yes, you should worry.

Nasdaq defines a bubble as “a market phenomenon characterized by surges in asset prices to levels significantly above the fundamental value of that asset.” Bill Conerly concurs in Forbes: “A bubble is a run-up in the price of an asset that is not justified by the fundamental supply and demand factors for the asset.” A bubble starts with confidence in the value of a thing, then expands as people invest in that thing, driving up its price and everyone’s growing enthusiasm. More and more people get in, but at some point the smart money gets out while the price for the thing is still high. Eventually, the value drops as everyone heads for the door. Prices go back down. Some people lose their shirts.

What would a coffee bubble look like? A coffee bubble might mean that consumer prices are impossibly high, and the bubble will burst when consumers wake up and start refusing to pay US$4.50 for their flat whites. Or, a coffee bubble might mean that there are too many brands in the market, creating consumer exhaustion and rebellion, collapsing the market back to a simpler time when there were fewer options. Or, a coffee bubble might mean that the big moves of big companies are built on false assumptions; those investments will fail to pay, and the resulting collapse of consolidation will ruin sectors of the industry that have grown to depend on them.

So, are we in a coffee bubble?

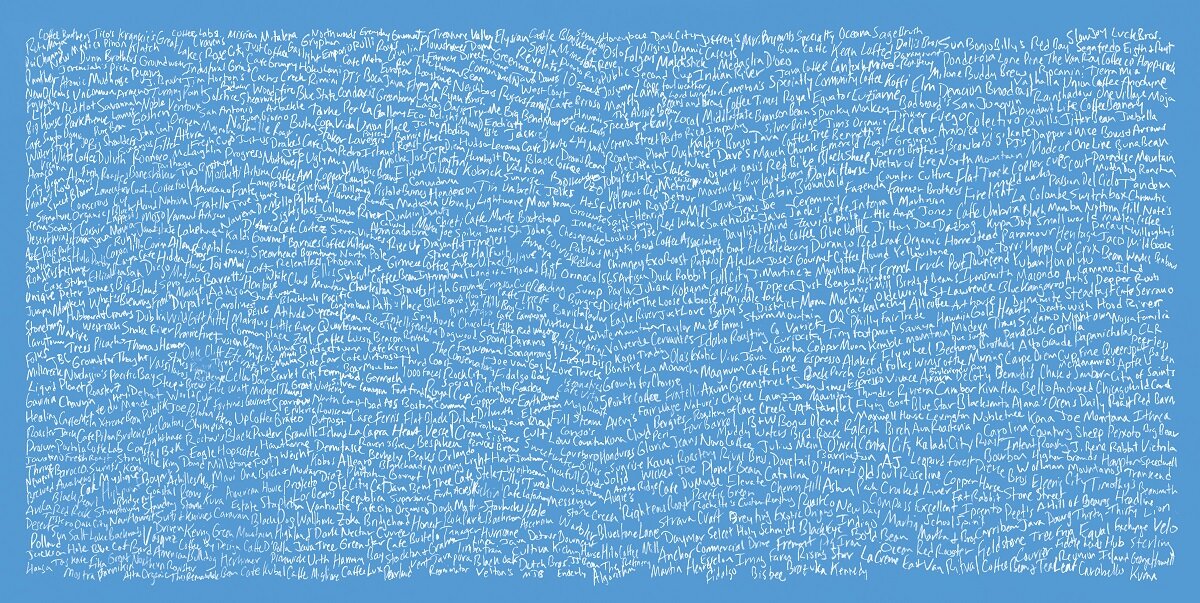

It is true that some markets are saturated with coffee, but an oversupply in the traditional locales of hip coffee only tells us that we have enough coffee in those hip places: it doesn’t mean we’ve got an oversupply everywhere. The truth is while the traditional centers for specialty coffee may be crowded, the base for specialty has grown much wider over the last ten years. Before 2008, the clear centers of the third wave in North America were the eight cities of New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, Vancouver, and Toronto. Since 2008, the third wave has spread out to nearly every city in North America: El Paso, Edmonton, Indianapolis, Orlando, Springfield, Franklin, Reno, Rockford. We see this trend in other countries, too: specialty is happening in Antwerp, Bristol, Leeds, San Sebastian, Riga, Tallinn. We dubbed this rise in the specialty waters “The Tidal Wave,” and as we look across North America, we see it percolating into every market where groups of people live.

Image (c) PQC 2018.

Our view is that the third wave is the creation of a haut-café form, with its own rules, qualities, tropes, and standards: single origin offerings, manual preparation, 18 gram doses, flavor language, sans-serif fonts, and minimalist design. The “tidal wave” represents the hegemonic supremacy of that form, the default go-to for anyone who wants to do something more upscale in their marketplace. And so, third wave is what everyone is doing because it’s what everyone is doing. This may be a bummer for people who enjoyed the third wave when it meant rare and exclusive, but cool and small creates its own fame and success. Well-prepared coffee is now as common as other things in the food business which weren’t always easy to find in smaller, more local markets: you don’t get this good stuff everywhere, but you can get it somewhere near you.

Broad availability is not a bubble – it’s democratic.

Further evidence of the mainstreaming of third wave values is the co-opting of craft language by the big brands: in a recent US television advertisement, new “Artisan Cafe” creamers are “crafted with Tahitian vanilla and Himalayan salted caramel and made with velvety milk, cream and buttermilk.” The creamer is pouring in a way that looks a lot like latte art. We aren’t fooled, but the message to people in coffee should be clear: these tropes aren’t exclusive to third wave specialists. Words like “crafted” and “origin” have leaked out to the general population. Special becomes general. Those of us who are in our third decade in specialty have seen this kind of thing before – there was a time when “gourmet,” “fresh roasted,” and “Italian” meant higher quality. After a time, those second wave indicators were generalized by their own success. The successful specialists of the second wave created their own mainstreams, and their language of difference turned into a language of the common.

There are absolutely legitimate risks to the coffee business. As coffee has spread, there are fewer and fewer places that are wide open for a better coffee offer (location, location, location). Climate change may decrease the supply of quality coffee or require it to grow in more expensive places. Shifts in the politics or economics in growing regions can influence costs and supply. Retail rents may go up. Consumer preferences will probably change. Regulations may force other changes upon the industry (think: cold brew). Retail itself is surely changing with the influence of the internet, shifting markets, and consolidation. These are real and legitimate risks, but they are not evidence of a bubble. Rather, they are elements that would go in the threats section of a fundamental SWOT analysis for the business of coffee. And that’s the point: this is a business, not a bubble. And yes, it’s business with a lot of risks.

There’s a cliché that “90 percent of all restaurants fail in the first year of business.” The real number, at least in the US, is around 30 percent in the first year, but the point is that the restaurant business is a difficult proposition. We think that if restaurants aren’t an exact analog, they are at least a very good metaphor for the challenges about which a coffee company should worry.

Think about your local restaurant market – if you live in a bigger town, you’re likely to find a mix of cuisines, small and large, chain and independent, casual and upscale, value-driven and pricey. This kind of choice-filled marketplace is robust and mature. We would argue that the coffee business is reaching similar maturity, perhaps 10 or 20 years behind the rest of the food marketplace. Like the restaurant business, most coffee markets now have a good mix of small and large, cheap and expensive, simple and exotic. In most places, the consumer has a broad range of coffee choices, from chain sources like Starbucks, 7-Eleven and McDonalds, to independent cafés of varying stripes and styles, including cafés exhibiting third wave characteristics. Consumers can satisfy their preferences from a rich menu and a selection of competing suppliers.

Coffee isn’t a tulip overvalued with cultural frenzy or a hyped-up silver lode that will run out. People in the coffee business shouldn’t worry about the collapse of a café confidence scheme or a sudden migration back to US$0.99 hot-and-bottomless. Instead, they should worry about relevance, market share, margin, their business plan, and their consumers. And this, finally, is the point: it’s not a bubble, it’s a rapidly maturing market. For better or worse, specialty coffee is now a competitive, risky business, with fickle consumers and small margins.

While it may sound harsh, not all businesses will survive this kind of market – and it’s not just about absolute failure. Even those businesses that make it to the two- or five-year mark may find low profitability a continuing challenge. So, if you want to give yourself the best opportunity for meaningful success, start with learning about the market and the consumer (macro to micro) and continue to build your management and business skills.

JAN ANDERSON is the President of Premium Coffee Consulting (PQC) where she works alongside DAN MCCLOSKEY, PQC’s Founder and Chief Creative Officer.

Historic Bubbles

We all lived through the real estate crisis of 2006 and 2007, but there is nothing new about speculative bubbles. Michael Pollan describes the 1637 European tulip bubble (yes, the flower) in his terrific book Botany of Desire, when the Dutch went from polite traders to frenzied speculators: Rushing to get in on the sure thing …people sold their businesses, mortgaged their homes, and invested their life savings in slips of paper representing future flowers. Predictably, the flood of fresh capital in the market drove prices to bracing new heights. On February 2, 1637, the bottom fell out. In one of the trading centers all at once every man in the room men who days before had themselves paid comparable sums for comparable tulips understood that the weather had changed.… Within days tulip bulbs were unsellable at any price.

Mark Twain points to his own experience with the silver bubble in 1858: I would have been more or less than human if I had not gone mad like the rest. Cart loads of solid silver bricks… were arriving from the mills every day, and such sights as that gave substance to the wild talk about me. I succumbed and grew as frenzied as the craziest.” (Twain 211). Like a lot of people, Twain got caught up trading in silver mine futures, hoping to strike it rich. Like the price of tulips, eventually silver collapsed, creating ghosts of thriving towns in the Nevada mountains.

Have you enjoyed Dan and Jan’s perspective on the state of the US market? You can read their recommendations for business building success here or find a recording of their Re:co Panel Discussion, The State and Future of the Business of Coffee.