Beyond Sugar and Milk: How Brazilians Pair Coffee with Food | 25, Issue 24

PhD student ANNA LUIZA SANTANA NEVES shares their research into Brazil’s everyday and culturally informed coffee and food pairings, from pão de queijo to chocolate.

Introduction by LAUREL CARMICHAEL, SCA Publications Manager

If you’ve ever been in Germany around 3 pm, particularly on a Sunday, you’ve likely encountered Kaffee und Kuchen Zeit (coffee and cake time). This mid-afternoon ritual is usually conducted with friends or family and is deeply entrenched in German society—it’s a time for gossip, indulgence, and family catch-ups. The coffee and cake pairings themselves are often regional; for example, Black Forest cake (Schwarzwalder Kirschtorte) comes from the region with the same name, while Lebkuchen, a spiced gingerbread, comes from Bavaria and is popular with coffee during the winter holidays. In Berlin, during Ramadan, you’ll often see people enjoying Turkish and Arabic coffee and tea with sweets after sunset.

The following article features Anna Luiza Santana Neves’ study on coffee and food pairing in Brazil. Neves used a mixed-methods approach to capture the complexity of pairings. The study utilized a freelisting approach to identify participants’ instinctive associations and a projective mapping approach where participants visually arranged photos of coffee and food to reveal “clusters” or common groupings that help us understand the myriad of reasons why and how people pair coffee with food.

This research reminds anyone who serves coffee and food—whether it be in a café or at a home-made brunch for friends—that combinations can do everything from evoking nostalgia to providing a morning pick-me-up to helping people display and define their own identity. The feature by Kosta Kallivrousis earlier in this issue (p.8) reminds us that digital natives are seeking experiences of co-creation and engagement with cafés, roasteries, and other coffee brands. Hosting food-pairing events—which Anna Luiza reminds us is deeply sentimental—is a great way to build real and lasting connections with customers. It’s also always fascinating to hear people’s associations with coffee and food—whether they align with ours or not! Maybe you could consider soliciting your communities’ food and coffee preferences on social media, or even hosting an in-person event centered around coffee, food, and storytelling.

Coffee is a symbolic and sentimental beverage, deeply embedded in many countries’ cultures and daily eating habits.

For example, in Italy, historic coffee culture has been shaped by espresso beverages and robusta. Turkish coffee, also enjoyed across the Middle East, is a symbol of hospitality and is often enhanced with aromatic spices, like cardamom or star anise.[1] In Ethiopia, coffee is embedded in centuries-old rituals, and is sometimes served with salt, butter, or tena Adam (rue) leaves.[2] Over the past two decades, the coffee sector in Brazil has undergone profound changes in consumer behavior, with consumers not only seeking higher-quality retail coffee, but also seeking a differentiated coffee experience. However, the predominant consumption is still of “traditional” coffee—typically with low sweetness and acidity and medium–high bitterness—and comparatively affordable retail coffee.

Brazil has approximately 125 million coffee consumers, representing more than half of the population. Coffee not only contributes to a national identity, it also transcends its commodity status to become a fundamental part of daily life. Beyond caffeine, it’s a source of pleasure and social connection: from breakfast to family gatherings.[3] These rich traditions show that coffee carries deep significance in different contexts—meanings that are enhanced further when it is paired with food. From traditional breakfast combinations to modern café experiences, the way we pair coffee with food is shaped by sensory compatibility, habits, and regional traditions. Mara V. Galmarini[4] and Charles Spence[5] highlight that food and beverage pairings are influenced by three main factors: chemical similarities, culinary culture, and aesthetic harmony. What’s more, we can organize these pairing traditions and conventions based on three ways we experience them: perceptual (how they taste, smell, and feel in our mouths); conceptual or intellectual (how we group or categorize them based on shared ideas or characteristics); and affective (what we like, prefer, or dislike). To understand how Brazilians pair coffee with food, and the complex social, cultural, and sensory factors that influence these pairings, we conducted a nationwide study using both online and in-person research.

The Study: Food Meets Coffee Across Brazil

Our research employed a mixed-methods approach, with the study divided into two phases. In phase one, we conducted an online survey where 300 participants were asked to identify culturally significant foods commonly associated with coffee. In phase two, we conducted an in-person activity known as projective mapping, where we asked 48 participants about their perceptions of certain coffee beverages. By combining these methods, this study provides a nuanced understanding of Brazilian coffee culture, contributing to sensory and consumer research.

Phase One: Consumption Habits and Free-Listed Food Associations

For our online survey, we used an interview technique known as free-listing. This technique is typically used to identify shared perceptions and concepts (known as cultural domains) rather than individual preferences. The results can then be analyzed to determine each item’s importance, prominence, familiarity, or cultural relevance.[6] We developed an online questionnaire using Google Forms and distributed it across Brazil’s five geographic regions: north, northeast, central-west, southeast, and south. These regions share certain cultural and gastronomic similarities, but also exhibit important differences due to Brazil’s large territorial span.

The questionnaire was divided into three sections. In the first section, we asked participants about coffee consumption habits, such as preference for traditional or specialty coffee, knowledge of coffee species (in this case arabica and robusta), preparation methods, and frequency of consumption. Only individuals who drank coffee daily were allowed to participate. The second section gathered basic socio-demographic information, including participants’ age, gender, region, and consumption habits. Our online survey revealed that while traditional coffee remains popular, there is growing interest in specialty coffee. Among the 300 respondents,[7] 67% were traditional coffee drinkers, while 33% reported consuming specialty or gourmet coffee. Of those who drank specialty coffee, 56% did so only occasionally.

When asked about coffee species, 39% said they consumed only arabica, while 32.2% were unaware of or indifferent to the species of coffee they usually consumed. Regarding preparation methods, 66.7% preferred Melitta® (a popular paper-filtered brewing method in Brazil), followed by espresso (53.8%). The survey results informed us that while Brazil still loves traditional coffee, young people are driving a shift towards habits and preferences we associate with specialty.

The third section of the survey aimed to gather participants’ associations between coffee and food. They were asked, as simply and specifically as possible, and without help from others, to “please list all the foods you think go well with coffee.”

Phase One Findings: Popular Coffee Pairings

The free-listing task generated 1,240 words related to coffee consumption. We selected foods that were mentioned by 10% or more of participants, resulting in a list of 14 foods (see figure 1).[8] The foods that were listed stood out because of multiple factors, including flavor, color, texture, personal associations and memories, and novelty. It was important to us that regional foods—such a pão de queijo (cheese bread), Brazilian corn couscous,[9] and tapioca—weren’t forgotten.[10]

Figure 1.

The top 14 foods that participants listed during the free-listing exercise, according to the frequency with which they were mentioned. [11] Only items that reached at least 10% of mentions are included.

We then took these 14 foods and grouped them into three main clusters based on their sensory and cultural connections to coffee, using a process called hierarchical cluster analysis (see figure 2). We found three groupings of food and coffee pairings, that we describe as: “comforting and traditional,” “versatile and regional,” and “indulgent and experiential.”

Comforting and Traditional Cluster

The first group includes carbohydrate-based foods that are simple and quick to prepare—such as bread with butter, pão de queijo, and homemade cake—commonly eaten for breakfast or as an afternoon snack. These foods combine the comfort of home cooking with everyday practicality, and most have been popular for a long period of time.

Versatile and Regional Cluster

The second group blends traditional and versatile items, spanning regional dishes and familiar breakfast options. It includes corn couscous, tapioca, toast, cake, bread, and cookies—mostly carbohydrate-rich. A key insight here is the similarity between couscous and tapioca, both culturally significant in the northeast of Brazil, with Indigenous and African roots.[12] Aside from cake, most of the foods in this group are typically savory, and many are versatile—for example, toast, bread, and crackers can be used as bases for different toppings. This cluster highlights foods that are starchy and adaptable, and that have a strong presence in Brazilian coffee habits.

Indulgent and Experiential Cluster

The third group comprises foods linked to pleasure and relaxation—typically consumed during breaks or as afternoon snacks. Examples include chocolate, cheese, cookies, sweets, and milk. These foods are often chosen because consumers like their sensory interaction with coffee. Milk products, for instance, soften coffee’s bitterness, acidity, and astringency. Sweets balance coffee’s bold flavors. Chocolate and cheese provide rich textures and intense flavors, making for interesting pairings. This group emphasizes that coffee is not just a breakfast drink—it’s also part of moments of pleasure and enjoyment.[13]

Figure 2.

This dendrogram is a way of grouping and clustering similar items. Here, foods (listed in figure 1) are placed in the dendrogram. The closer they are to each other on the vertical (y) axis, the more similar they are. Each food listed at the bottom is a “leaf” of the dendrogram, and foods are connected to form clusters. There are three clusters here, marked in red (comforting and traditional), light blue (versatile and regional), and purple (indulgent and experiential).

Phase Two: Mapping Coffee Preferences

The main objective of Projective Mapping (PM) was to compare different coffee-based beverages based on participants’ perceptions. This technique enabled us to visualize how different types of coffee beverages—such as espresso, filtered coffee, cold brew, and milk-based coffee drinks—are positioned within a shared sensory and conceptual space and how they relate to the three clusters of food we identified (see figure 3).

In this stage, 48 volunteers were recruited via Google Forms. The group included students, staff, and professors from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), as well as other coffee consumers from the city of Campinas—a university hub that attracts people from across Brazil, providing a degree of regional diversity. We gave each participant a sheet of paper and labeled photos of 11 different coffee beverages—espresso, cold brew, espresso lungo, paper-filtered brewed coffee, cloth-filtered coffee, ristretto, French press coffee, coffee frappé, mochaccino, cappuccino, and milky coffee. We asked them to evaluate each of the 11 coffee beverages, based on the beverages’ sensory qualities, the participants’ likes or dislikes, and the contexts in which they are consumed. Based on these factors, we instructed participants to “place those that are similar close together” and “those that are different further apart.”

Figure 3.

A multiple factor analysis (MFA) visualization of the projective mapping exercise. Participants first placed the names of different coffee beverages (shown in blue) on the map. The closer the blue dots are together, the more similar the participants perceived the beverages. Participants then added foods (shown as red dots) close to the coffee beverages that they associated them with.

Next, we provided a set of 12 cards, containing the names of foods selected based on their ranking in the free-listing task.[14] Participants were instructed to “analyze the foods based on their sensory characteristics and how suitable they are for consumption with coffee,” and place the food cards closest to the beverages they best complement. If they believed that a food didn’t pair well with any beverage, they were instructed to position the card further away. Participants were given the option to rearrange the cards as they went, reflecting their flexible calculus of which foods paired with different beverages. They could also write additional notes to describe or name any groups, pairs, or clusters that emerged.

Coffee as a Sensory Language

The projective mapping technique provided a clear visualization of how participants perceived differences between black coffees and milk-based coffees. Coffees with milk were consistently grouped on the right side of the maps, while filtered and black coffees were grouped on the left. These groupings reflected perceived similarities among the beverages. Cold brew formed a separate cluster, likely because it is still relatively new in Brazil and perceived as different—both in flavor and in its appeal to a niche audience.

When foods were included in the mapping activity, they were almost exclusively associated with black coffees—particularly starch-rich items like pão de queijo, bread (with or without butter), toast, and cake. Foods that we categorized as “indulgent and experiential,” including chocolates, cookies, and other sweets, were clustered together, closer to beverages such as “ristretto” or “lungo.” Interestingly, no food was associated with milk-based coffees or cold brew, indicating that these pairings are not yet culturally or sensorially established.

Cheese, however, appeared near both filtered coffee and espresso, which makes sense from both a sensory and a cultural standpoint. The bitterness of black coffee is balanced by the fat and umami in cheese, creating a pleasant contrast. Culturally, cheese is a common part of Brazilian breakfasts—often in sandwiches—reinforcing this familiar pairing.

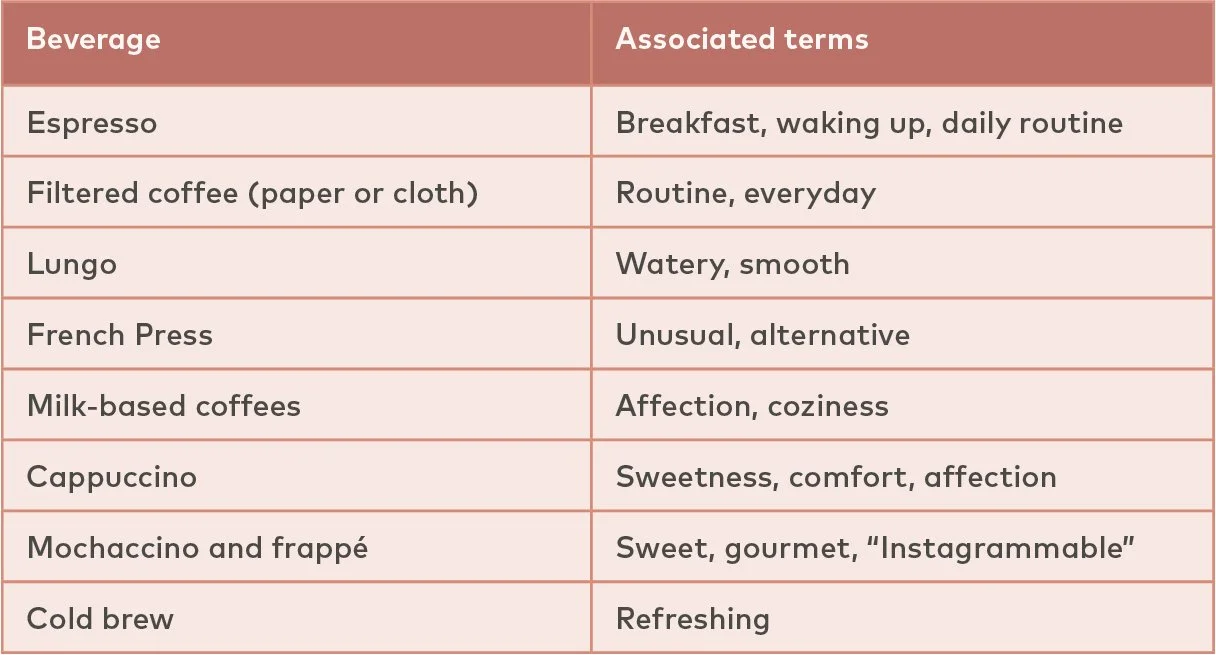

Figure 4.

A table showing coffee beverages and the descriptive words and experiences that study participants associated with them.

After arranging the cards, we invited participants to write down descriptive words based on their experiences and impressions. When we analyzed these responses using a process called triangulation, we were able to match beverages with their associated characteristics (see figure 4). These descriptions mirror some of the food clusters we identified, and show how our perceptions of coffee combine flavor, emotion, and cultural associations—all of which influence how we choose and enjoy different coffee types. Understanding these pairings can help cafés, restaurants, and retailers craft menus and marketing strategies that reflect local traditions while appealing to global trends.

Food and Coffee Pairing: A New Frontier for Specialty Coffee?

For cafés, roasters, and retailers, understanding these pairings offers insight into how to design menus, recommend pairings, and connect with consumers at a deeper level. In Brazil, coffee pairing is not driven by gourmet rules, but by lived experiences, cultural memory, and emotional cues.

The next frontier in specialty coffee may be not only how we drink it, but what we eat with it and why. As coffee-drinking habits differ between regions and generations, there is no single version of a perfect coffee and food pairing and there is room for cafés, restaurants, and retailers to help build new, positive associations. The lack of associations between cold brew and milk-based coffees with food in our study, for example, demonstrates an opportunity for innovation in the Brazilian market.

Personally, I enjoy pairing coffees with fruity profiles with pão de queijo, because I think higher acidity coffee balances the fat of cheese. We already know the classic pairing between coffee and chocolate, but I found recently that the sweetness and delicate acidity of ruby chocolate was especially delicious in balance with robusta’s bitterness. These pairings are driven by my sensory preferences, but also by cultural familiarity and the joy of new discoveries. They remind us that pairing with coffee is not just a sensory practice, but also a personal and cultural journey in constant transformation. ◊

ANNA LUIZA SANTANA NEVES is a PhD student at the Department of Food Science and Nutrition at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Brazil. Their research explores the intersection of sensory science, food culture, and consumer behavior in the context of Brazilian coffee traditions.

References

[1] Serkan Yiğit and Nilüfer Şahin Perçin, “How Would You Like Your Turkish Coffee? Tourist Experiences of Turkish Coffee Houses in Istanbul,” International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 15, no. 3 (2021): 443–454, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-11-2020-0274.

[2] Messenbet Geremew, Neela Satheesh, and Solomon Workneh Fanta, “Role of Coffee in Ethiopian Ethnic Culture–A Coffee Festival,” 2nd International Conference on Coffee and Cocoa (2022).

[3] Camila R. Arcanjo Teles and Jorge H. Behrens, “The Waves of Coffee and the Emergence of the New Brazilian Consumer,” in Coffee Consumption and Industry Strategies in Brazil, 1st ed., edited by Eduardo Eugenio Spers and Luciana Florêncio Almeida (Woodhead Publishing, 2020), pp. 257–274; Lilian Maluf de Lima et al., “Behavioral Aspects of the Coffee Consumer in Different Countries: The Case of Brazil,”

in Coffee Consumption and Industry Strategies in Brazil.

[4] Mara V. Galmarini, “The Role of Sensory Science in the Evaluation of Food Pairing,” Current Opinion in Food Science 33 (2020): 149–155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2020.05.003.

[5] Charles Spence, “Food and Beverage Flavour Pairing A Critical Review of the Literature,” Food Research International 133 (2020): 109124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodres.2020.109124.

[6] Caitlyn Placek, Eric Budzielek, Lillian White, and Deanna Williams, “Anthropology in Evaluation: Free-Listing to Generate Cultural Models,” American Journal of Evaluation 45, no. 2 (January 2023): 109821402211160, https://doi.org/10.1177/10982140221116095.

[7] The majority (60.4%) of our survey respondents were women; 41.8% were aged between 25 and 35 years, and 58.2% held a graduate degree.

[8] In addition to measuring the frequency with which foods were mentioned, we studied the order (or rank) in which they were mentioned, and measured their cognitive salience index.

[9] Brazilian corn couscous is one of the most iconic and beloved dishes in Brazil, especially in the northeast region. Simple, versatile, and full of flavor, it is made with corn flakes, hydrated and steamed, usually in a couscous maker. It is eaten for breakfast or dinner, or as a side dish with other dishes.

[10] National Geographic Brasil, “Qual é a origem do pão de queijo?” (August 2024),

https://www.nationalgeographicbrasil.com/cultura/2024/08/qual-e-a-origem-do-pao-de-queijo.

[11] Brazilian sweets: small, traditional treats that are often served at parties. They are characterized by their individual size, soft or creamy texture, and strong flavors—usually made with condensed milk, coconut, chocolate, or peanuts.

[12] Luís da Câmara Cascudo, História da Alimentação no Brasil, 4th ed. (Global Editora, 2004).

[13] Gianluca Donadini, Maria Daria Fumi, and Milena Lambri, “A Preliminary Study Investigating Consumer Preference for Cheese and Beer Pairings,” Food Quality and Preference 30 (2012): 217–228, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodqual.2013.05.012; Thomas F. Lüscher, “Wine, Chocolate, and Coffee: Forbidden Joys?,” European Heart Journal 42 (2021): 4520–4522, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab654; Charles Spence, “Multisensory Flavour Perception: Blending, Mixing, Fusion, and Pairing Within and Between the Senses,” Foods 9, no. 4 (2020): 407.

[14] “Milk” was excluded because it was already present in milky coffee beverages, and “plain cake” was omitted because “cake” alone was considered sufficient to represent that category.

We hope you are as excited as we are about the release of 25, Issue 24. This issue of 25 is made possible with the contributions of specialty coffee businesses who support the activities of the Specialty Coffee Association through its underwriting and sponsorship programs. Learn more about our underwriters here.