All in the Mind: How External Cues Impact Brain Activity and Preference | 25, Issue 18

Corresponding author MATEUS MANFRIN ARTÊNCIO shares the findings of a recent paper, “A Cup of Black Coffee with GI, please! Evidence of Geographical Indication Influence on a Coffee Tasting Experiment,” published in Physiology & Behavior, confirming the significant influence an extrinsic attribute like a geographical indication has on consumers’ tasting.

I’ve been fascinated by research on the human brain for as long as I can remember—it’s so integral to everything we do, think, and feel, but we are only just beginning to unpack the mystery of how it all works. An innately complex organ that inspires deep philosophical questions about identity formation, points of view, and humanity itself? Sign me up!

While “willingness to pay” studies have offered insights into the role external attributes play in coffee choice, the paper covered in this next feature takes things a few steps further. Mateus Manfrin Artêncio, Janaina de Moura Engracia Giraldi, and Jorge Henrique Caldeira de Olivera confirmed the impact the mere presence of an extrinsic attribute—in this case, even the simple act of implying a coffee had come from a particular kind of location—has on a coffee drinker’s cognitive processing while they taste coffee. While this is an exciting confirmation of the importance (and value) of external attributes in personal coffee preferences, this paper (for me, at least) raises a lot more questions than it answers.

First, and perhaps broadest, what role do the concepts of nature and nurture play in how the participants’ brains reacted to both the coffee’s sensorial properties and the external attribute cue the researchers gave? If the 1990s were “the decade of the brain,”[1] during which we made our first great leap in neurological and behavioral science research, how much more nuanced and complex might our understanding of this very topic be in another 10, 20, or 50 years? What is the role and importance of consumer education (in this case, when the researchers gave a brief explanation of the external attribute before tasting) in how any attribute is received and interpreted? Would the participants respond in the same way to the attribute if they didn’t know what it was?

Regardless, I find it incredibly exciting that we’ve reached a stage where this kind of research is being conducted specifically on coffee. The idea that we can measure human response to specific attributes—beyond self-reported responses—is fascinating. And, perhaps most relevant to the SCA’s work on a Coffee Value Assessment System (see this, this, or this), it further confirms the thread of logic around why sensory testing best practice is to avoid combining different types of tests together: when we taste a coffee, any extrinsic information we have available impacts not only our preferences, but our brain’s intake and interpretation of that coffee’s (intrinsic) sensorial properties.

Jenn Rugolo

Editor, 25

If we’re only able to build our opinion on a coffee’s aroma, taste, and mouthfeel as we consume it, how can we effectively communicate what’s inside the packaging—and set expectations we’ll be able to meet—while it’s still on the shelf?

While you may not be familiar with the idea of “Signaling Theory,” you’re impacted by it every day, and likely already use elements of it in your work.[2] Elements of package and label design—known as extrinsic information—like brand name, logos, taste descriptors, country of origin, and sustainability or health labels all act as “signals,” or a way to communicate expectations to customers. Signaling theory, the broad exploration of how we use and interpret these signals to make decisions around everything from gauging our safety to purchase decisions, has emerged as a research stream focused on signaling in product markets (e.g., how elements of marketing mix act as signs of quality to consumers).[3]

As coffee consumer demand for greater quality and differentiation increased, particularly by adopting of ideas of “craft” and increased transparency around producers and origin, the use of Geographical Indications (GIs) as a signal has become more common. First created as a kind of intellectual property, GIs legally protect traditional foods that have a strong bond with a place’s natural and human characteristics (i.e., terroir and savoir-faire, respectively). DOC Parmigiano-Reggiano, Vidalia onions, Prosciutto di Parma (Parma ham), and Champagne are all examples of foods protected under the GI system. It didn’t take long for some coffee producers, seeing GI as a marketing strategy already used in other specialty food products, to realize that establishing GIs for coffee could evoke consumers’ mental imagery of a place (some examples you may be familiar with include Hawaiian Kona, Guatemala Antigua, or Jamaica Blue Mountain).[4] The use of a GI might also confirm the relationship between origin (or terroir) and coffee, indicating that it may present high-quality and unique properties during consumption—and prior research exploring the effects of GI labeling on consumer behavior have found a positive effect on willingness to pay, consumers’ acceptance, and perception of sensory attributes.[5],[6]

As signals are only effective if the signal receiver (in this case, a consumer) responds to the information provided, we wanted to understand the impact of a GI cue on consumers. But consumer research is tricky—differences between stated and revealed preferences (what people say they prefer versus what we can infer they prefer through their actions) can be vast, and changeable in context. We wanted to avoid the limitations that traditional data collection methods, like questionnaires or interviews, might present. (For instance, when answering a questionnaire, people tend to form rational filters and are restricted by language barriers or shyness, which will bias responses.) Instead, we chose a neuroscience tool for data collection—electroencephalography (EEG)—to record consumers’ brain activity while participating in a coffee tasting experiment. Once we’ve explored the neuropsychological mechanisms underlying these responses, a neuroscience approach enables us as researchers to fully capture consumer responses (conscious and unconscious).[7]

Interpreting the Language of Brainwaves

Thanks to the progress in imaging techniques, processor technologies, and data analysis procedures, we’ve been able to deepen our knowledge of the human brain and understand how it shapes our perceptions and interactions with the world. EEG, an imaging technique that measures and records brain activity, is one of the most versatile consumer neuroscience tools.[8] Etymologically, “electro-encephalo-graphy” means “writing of the electric activity of the brain”; in practical terms, EEG equipment records the brain’s electrical activity using electrodes placed on the head, identifying how neurons in different brain portions communicate with each other via electrical impulses.

Figure 1. Types of brainwaves.

As in other types of reading and writing (e.g., poem, novel, scientific paper), when using EEG to collect data, it is important to define an appropriate (and mutually understood) vocabulary, surface, writing instrument, etc. Beyond using the right equipment and software, brain regions, waves, and analysis techniques are also key points for consideration if we’re hoping to interpret brainwave activity. The vocabulary of neural oscillations, a mixture of several underlying base frequencies, is incredibly important, as these frequencies are considered to reflect cognitive, affective, or attentional states. Because these frequencies or waves may vary due to individual factors, they are classified in ranges: delta band (1–4 Hz), theta band (4–8 Hz), alpha band (8–12 Hz), beta band (13–25 Hz), and gamma band (> 25 Hz).[9] As shown in Figure 1, waves can be correlated to individuals’ internal states.

Bearing all this in mind, we assumed that the coffee’s GI cue would possibly affect consumers’ cognitive processing (i.e., how participants’ brainwaves would be influenced by coffee tasting and the presence of the GI cue). Our first hypothesis: origin information, presented as a GI cue, would affect participants’ brainwave oscillations. As we were familiar with Signaling Theory and consumers’ positive responses to origin information, we also wanted to test if the mention of origin information would induce preference in participants. (We guessed, in another hypothesis, that participants would prefer the coffee with a GI cue over the coffee without it.)

In consumer behavior research, product involvement—how important or interesting a product is to a consumer—is often included in studies because of its influence as a moderator, or ability to impact how a consumer receives and acts upon information. Another way to think about this is: if you are regularly engaged in coffee preparation and consumption, search for coffee knowledge, or participate in coffee-related communities, you have “high product involvement, and you are more likely to consider (and act on) product information in your assessment of different coffee packaging you see on the shelf. Product involvement can be high, when the product category is relevant to the consumer, or low, when the product category is not important. As prior studies have identified that consumers who have different levels of product involvement will have significant differences in brain activity when responding to food stimuli, we also hypothesized that consumers who had a high involvement with coffee would respond differently to a GI cue than consumers with a low involvement in coffee.

Taste Test

Figure 2. Illustration of the blind coffee tasting experiment.

To test these hypotheses, we designed a blind coffee tasting experiment: while tasting two samples of the same coffee, participants would have their brain activity recorded. To understand the impact of the origin cue on participants, we offered one sample without any origin information, and the other as being from a place with a Geographical Indication. After answering a questionnaire on health, demographics, coffee consumption and product involvement, participants were connected to the EEG, which monitored 10 EEG channels[10] and four brainwaves[11] to measure the effects of origin information.

We served the first sample, offered without any GI information, before asking the participant to read a simple explanation of Geographical Indications. After reading, we told the participants that the next sample for tasting came from a GI, but we didn’t associate it with any specific region. Participants were not aware that it was the same coffee being served twice. A glass of water was served to all participants before each coffee sample, for cleansing the palate and to avoid carry-over taste effect. At the end of the tasting section, we asked the participants which coffee they preferred.

What We Learned

Before we share the results, it’s important to note why we’re presenting the following information across two general gender categories, men and women. Gender, “a complex interrelationship between a person’s body, identity, and social gender,”[12] is a demographic variable often included in studies concerning food, consumers’ responses, and neuromarketing. While breaking results down across gender and biological sex is more complicated than the resulting implied binary, it does allow for a more nuanced understanding of the results. Recently, in a blind tasting EEG experiment with wines, researchers’ analysis of all the participants’ brains in a single group showed no differences in cognitive processing or preference, but when grouped by gender, enabled the researchers to track differences in emotional brain activity (in the delta brainwave).[13]

So, what of our hypotheses? We found our first—that receiving the GI cue would cause changes in participants’ brains—to be true. Fig. 3 shows the activation of different channels and waves upon receiving the GI cue. Both male and female participants experienced brain activation in the right hemisphere of the brain, although the effect of the GI cue appeared more intensely in female participants. This finding further supports signaling theory, confirming that the extrinsic cue was interpreted as an important cue by participants, as evidenced by their brain activity.

To verify our second hypothesis, that a GI cue would also indicate preference, we focused on comparing the averages of delta and theta waves, which are associated with states of relaxation, pleasantness, and motivational responses in previous research. We observed two opposing outcomes: on one hand, men presented higher averages of delta and theta waves for the coffee with the GI cue, which indicates the preference of this group; on the other hand, women presented higher average delta and theta wave values for coffee without the GI cue. In other words, each group preferred a different coffee; therefore, this hypothesis could not be confirmed, since we expected that both would prefer the coffee with the GI cue.

Despite these EEG results, when asked about their preference at the end of the experiment, 29 of the 40 participants said they preferred the sample with a GI cue. We think this may be evidence of some of the limitations of more traditional consumer data collection methods such as surveys or interviews, and interpreted this as an indication that participants may have rationally answered this question by indicating their preference for a supposedly superior product.

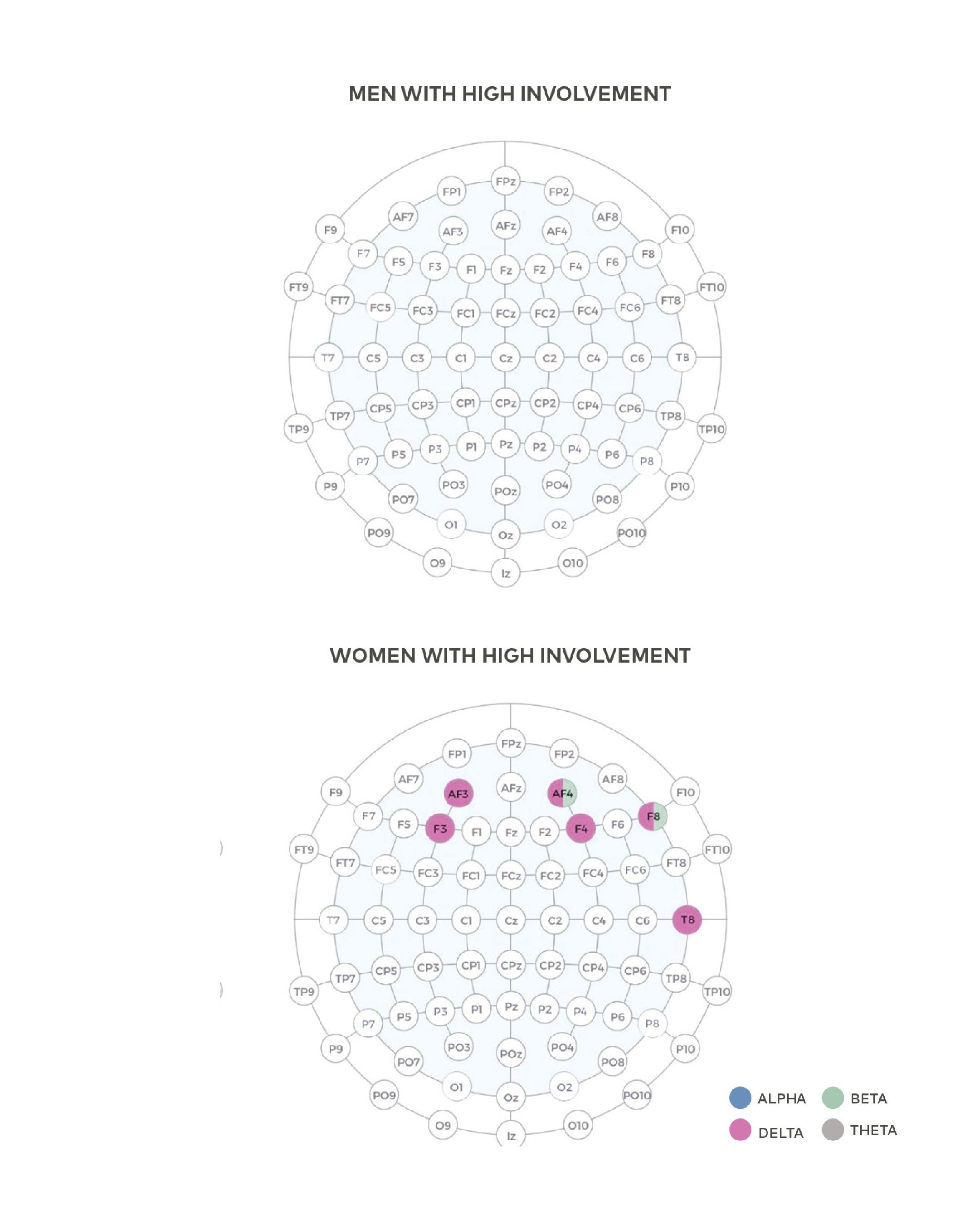

To test the third hypothesis—participants with different levels of involvement would react differently to a GI cue—we needed to split the groups according to their survey responses on their level of involvement. Fig. 4 presents brain differences observed in participants with low involvement, while Fig. 5 illustrates brain differences in participants with high involvement.

Figure 3. Activation of different channels and waves in participants' brains after receiving the GI cue; more different kinds of waves were activated in more different parts of the brain among women participants.

Figure 4. Brain differences observed in participants with low involvement.

Figure 5. Brain differences observed in participants with high involvement.

Interestingly, Fig. 4 shows that both men and women with low coffee involvement had most activation on the left side of their brain, and like earlier figures, the effect of the GI cue on the women’s brainwaves was greater. Conversely, Fig. 5 shows almost no change in the brain activity of men with high involvement, but significant differences across both brain areas and waves of women with high involvement. This meant our third hypothesis about differences in the response of consumers with different levels of involvement was also supported.

What Does It All Mean?

These results make it clear that an extrinsic attribute like a GI cue has the potential to communicate the reputation and quality characteristics of coffee products linked to a geographical origin. However, there are several hurdles to establishing this potential benefit, as many product categories and places would need to first improve their product’s origin communication and signalization. Registration and maintenance of a GI label also requires the support of pre-existing producer collective organizations and the public. But given their potential to act as an important lever for economic development, the exploration of their use is still encouraged.[14]

Our results did not generate a strong predilection for the GI coffee across all groups, and this is at odds with previous research in this area, which indicates that participants prefer products with the extrinsic cue of a highlighted origin. There were several possible reasons for this result: perhaps our use of the same coffee in both tests, the novelty of the term GI where we conducted our experiment (Brazil), and participants’ limited knowledge of GI cue may have been why our results weren’t in keeping with the literature.

Instead, we observed that involvement level had a bigger impact in how participants’ brains responded to the GI cue, an indication that participants with distinct involvement levels are influenced differently by origin information. We found this observation to be most intense for women: their involvement level presented greater influence as a moderator because differences between tastings were found in more brain areas and waves (the only significant difference between men with high and low involvement was found in a single EEG channel and wave).

While our sample was small (larger samples are difficult to manage in neuroscientific studies!), we found the mere mention that the coffee came from a GI—without relating it to any specific region or logo—was sufficient to elicit different brain responses in participants, confirming that extrinsic attributes can influence consumers’ tasting experience. Although there’s still more to learn and explore in future research, we also established that different perspectives—whether based on product involvement or gender—also impact how these kinds of external cues are received, interpreted, and used. This confirms that specialty coffee’s existing use of tools to build a specific product identity or image through country of origin or region (in addition to farm, cooperative, or microlot) helps to achieve price premia and product differentiation. However, as more and more product options become available (that is, there are more and more potential external attributes), it’s important to also keep in mind that consumers are subject to information overload while purchasing. As uncertainty in product evaluation increases consumers’ usage of extrinsic cues, a more potentially relevant cue, such as GI and other origin dimensions, can be used to counter issues of unknown external attributes and facilitate decision-making. Food for thought as you design or refresh your packaging! ◇

MATEUS MANFRIN ARTÊNCIO is a PhD student in Business Administration at Universidade de São Paulo and was the corresponding author on the paper “A Cup of Black Coffee with GI, Please! Evidence of Geographical Indication Influence on a Coffee Tasting Experiment,” published in Physiology & Behavior, with co-authors JANAINA DE MOURA ENGRACIA GIRALDI and JORGE HENRIQUE CALDEIRA DE OLIVERA.

References

[1] US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Brain Basics: Know Your Brain, NINDS, last reviewed June 25, 2022.

[2] To learn more about signs and signals in specialty coffee shop aesthetics and environments, see Andre Theng’s “When the Signs Point to Coffee” in Issue 15 of 25, https://sca.coffee/sca-news/25/issue-15/when-the-signs-point-to-coffee.

[3] Valdimar Sigurdsson, Nils Magne Larsen, Rakel Gyða Pálsdóttir, Michal Folwarczny, R.G. Vishnu Menon, and Asle Fagerstrøm, “Increasing the Effectiveness of Ecological Food Signaling: Comparing Sustainability Tags with Eco- Labels,” Journal of Business Research 139 (2022): 1099–1110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.052.

[4] For a deep dive into the concept of Geographical Indications and how they intersect with coffee, see Ruth Hegarty’s “Protecting Terroir” in Issue 3 of 25, https://sca.coffee/sca-news/25-magazine/issue-3/protecting-terroir-25- magazine-issue-3.

[5] Chun-Chu Liu, Chu-Wei Chen, and Han-Shen Chen, “Measuring Consumer Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Coffee Certification Labels in Taiwan,” Sustainability 11, no. 5 (2019): 1297, https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051297.

[6] Elisabetta Savelli, Laura Bravi, Barbara Francioni, Federica Murmura, and Tonino Pencarelli, “PDO Labels and Food Preferences: Results from a Sensory Analysis,” British Food Journal 123, no. 3 (2021): 1170–1189, https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2020-0435.

[7] Letizia Alvino, Luigi Pavone, Abhishta Abhishta, and Henry Robben, “Picking Your Brains: Where and How Neuroscience Tools Can Enhance Marketing Research,” Frontiers in Neuroscience 14 (2020), https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.577666.

[8] Alvino et al., “Picking Your Brains.”

[9] Karina Munari Pagan, Janaina de Moura Engracia Giraldi, Vishwas Maheshwari, André Luiz Damião de Paula, and Jorge Henrique Caldeira de Oliveira, “Evaluating Cognitive Processing and Preferences Through Brain Responses Towards Country of Origin for Wines: The Role of Gender and Involvement,” International Journal of Wine Business Research 33, no. 4 (2021): 481–501, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-08-2020-0043.

[10] AF3, F7, F3, FC5, FC6, F4, F8, AF4, T7, and T8.

[11] Alpha, beta, delta, and theta.

[12] Understanding Gender, Gender Spectrum, https://genderspectrum.org/articles/understanding-gender.

[13] Pagan et al., “Evaluating Cognitive Processing and Preferences.”

[14] Xiomara F. Quiñones-Ruiz, Marianne Penker, Giovanni Belletti, Andrea Marescotti, Silvia Scaramuzzi, Elisa Barzini, Magdalena Pircher, Friedrich Leitgeb, and Luis F. Samper-Gartner, “Insights into the Black Box of Collective Efforts for the Registration of Geographical Indications,” Land Use Policy 57 (2016): 103–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.05.021.

We hope you are as excited as we are about the release of 25, Issue 18. This issue of 25 is made possible with the contributions of specialty coffee businesses who support the activities of the Specialty Coffee Association through its underwriting and sponsorship programs. Learn more about our underwriters here.